- Interview

vol.03

Lacquer x the streets! ? The lacquer shop Tsutsumi Asakichi Urushi, which takes lacquer, a material that has been loved since Jomon times, to the next generation

Dive into Material #3

In this issue, we discuss lacquer, a natural material that has been deeply connected with the lives of the Japanese people. When we think of lacquer, the tendency is to think of luxury goods that are a bit awkward to use in daily life, such as lacquered vessels and high-class furniture. You may not know, however, that there are guys who dash about Kyoto on lacquered skateboards and lacquered bicycles?

A skateboard, which is used on the street and get covered in scratches, and lacquer, a material synonymous with luxury goods—while this combination might seem inconceivable at first, we uncovered the surprising reason for its existence.

Kinoshita from MTRL KYOTO spoke to Takuya Tsutsumi, managing director of Tsutsumi Asakichi Urushi lacquer shop in Shimogyo Ward, Kyoto and someone who is pursuing the new possibilities of lacquer.

- Takuya Tsutsumi. Tsutsumi Asakichi Urushi, a shop that refines and sells lacquer, has a history of over 100 years.

Lacquer trees, which take over 10 years to grow

—I understand that your shop, Tsutsumi Asakichi Urushi, both refines and sells lacquer. First of all, could you talk to us about the process through which lacquer comes into being?

Tsutsumi: Lacquer trees come mainly from Asia. Trees are planted mainly in Southeast Asia, including countries like Vietnam, but also Japan and Taiwan. The compounds included in the lacquer trees differ depending on the species and the region from which they come. In Japan, famous production regions are Iwate and Ibaraki prefectures. It takes 10 to 15 years before sap can be collected from the trees.

- A lacquer tree after scratching. Depending on the time that it is harvested, the sap is divided into types known as hatsuhen, sakari, suehen, and urame.

―I understand that it takes a long time for sap to come to be produced in the wood.

Tsutsumi: Sap is collected each year from about mid-June to late-October. This is known as urushi-kaki in Japanese. The surface of the tree is cut, and the sap that oozes out is collected by being scraped off with a spatula. Only 200g can be taken from a single lacquer tree, collected over a period of 5 months.

- Well-known lacquer production areas include Joboji Temple in Iwate. Only 3% of lacquer produced in Japan comes from sources in Japan, and of that, 70% comes from Iwate.

Tsutsumi: We refine lacquer using tubs of lacquer delivered to us from such production areas. So let’s go take a look at the factory.

Tsutsumi: The first step is urushi-koshi, or straining of the lacquer. Arami (the newly collected sap that is sent to us from the production area) is put in a hot water pot and is strained. Next, a straining cloth is placed in the arami to collect impurities in a process called kakuhan-nerikomi. Finally, the material is put in a centrifugal machine to filter it and create ki-urushi or basic lacquer.

- Agitation and mixing are performed using this machine.

- Finished basic lacquer.

Tsutsumi: Raw lacquer is used in that state as a base and is applied using a brush or a spatula. If you want to refine it, you place the raw lacquer in the mixer and perform an agitation process known as nayashi, and a process known as kurome, which removes the excess moisture content. The luster and viscosity of the final lacquer depends on the time and speed of the mixing that happens during nayashi while the dryness of the lacquer is decided by the length of time heat is applied during kurome.

―How is colorful lacquer made?

Tsutsumi: Colored lacquer is made by adding a pigment to clear lacquer, whose transparency has been increased by slowly heating up basic lacquer and adjusting its moisture content.The way the lacquer dries and the way that the color changes through time are rather interesting.

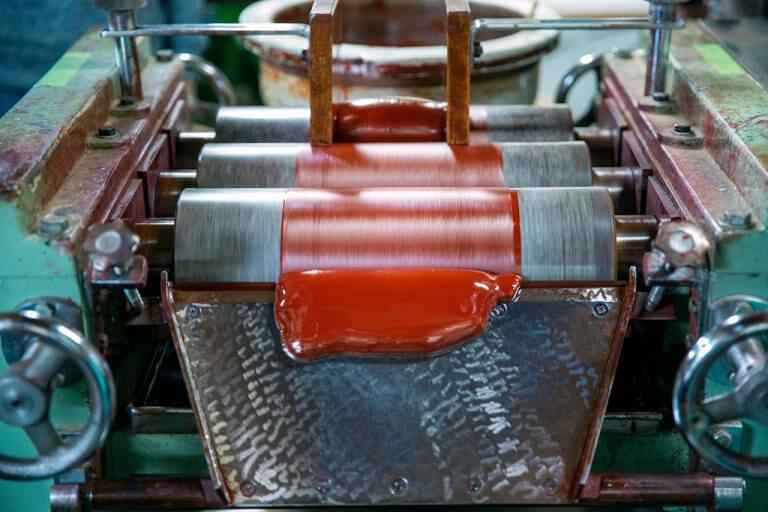

- After roughly mixing the clear lacquer and the pigment, a triple roll mill is used to ensure the pigment is thoroughly dispersed.

―I was not aware that this number of processes were involved in the creation of lacquer.

Tsutsumi: Even using lacquer purchased from the same production area, the final finish will differ depending on the temperature and humidity on the day you are refining the lacquer. We collect and save data each day in order to check the dryness and luster of the lacquer.

- To be able to supply customers with the kind of lacquer that suits their purposes, the shop measures things like the luster, drying time, transparency, and viscosity of the test coat and keeps data.

To find out more about the lacquer refining process, please see this video.

A material that combines strength and gentleness

―Next, I would like to ask about the functionality of lacquer. The typical image of lacquer is of something weak, something that tends to wear thin easily, but is this actually the case?

Tsutsumi: Lacquer is a natural high polymer and it’s surprisingly strong. A lacquer coating is harder than a urethane coating and is not affected by either acidic or alkaline substances. On the other hand, many people have the impression that lacquer is something moist, something like baby skin. Normally, if you touch some kind of hard coating, you would perceive it as hard or cold, but with lacquer, many people have an impression of it as being soft, which is interesting.

―Although lacquer is strong, it’s a material that people find very compatible!

- Kinoshita from MTRL KYOTO

Tsutsumi: Personally, I think that the way our feelings change when we use lacquer is one of the functions of this material. There are some kindergartens that use lacquerware bowls, and the bowls are treated carefully so that the children can enjoy holding them in their hands. When they first started using the bowls, the teachers would wash them in the dishwasher, but now they wash them by hand. So the way our feelings change and our behavior becomes more beautiful as we use lacquerware objects is also one of the functions of lacquer, I feel.

―I think that the functionality of the material is in things that cannot be analyzed by science or that cannot be quantified. Thinking about it like this, one of lacquer’s functions is also using it for a long time, fixing it yourself.

―The nature of the lacquer changes depending on the production area and conditions on the day it is refined. Please tell us about your method for accepting orders.

Tsutsumi: We tailor make, according to the craftsman. The situation is that the everyone using lacquer will have a completely different standard, so we control the dryness and the viscosity depending on the kind of lacquer that particular craftsman is after.

- Checking the transparency and dryness, and writing the date that the lacquer was refined and its special features on each of the tubs.

―I had thought that lacquer was a material that was difficult to handle, but it seems that it’s something that can be controlled to quite an extent.

Tsutsumi: That’s right. We, of course, control things to some extent, but we also work on the premise that the craftsman that is going to be using the lacquer will be exercising controls. A lot of people think of lacquer a mysterious material, but once you get a sense of the drying speed, it’s a material that you can definitely work with.

―Recently, the importance of CMF design— CMF standing for color, material, and finish— is increasingly attracting attention in the manufacturing of products and the selection of materials. For example, when you want to communicate the softness of the material, you can express the idea with Japanese onomatopoeia or using a simile like “soft as a Turkish delight,” but everyone is going to imagine something different. However, in the world of lacquer, in addition to matters of color and texture, I feel that there is a rich variety of words and expressions—to describe things like processing characteristics (the ease with which the lacquer goes on, the ease with which it dries)—that exist to create a common ground of understanding when it comes to using the materials. Creating an order-made product in response to abstract orders from craftsmen as a matter of course, as you do, is actually something quite fresh in today’s world of increasing mass production and industrialization. I imagine that there would be a demand for what you do in different situations.

- In the lacquer industry, words such as “hayai,” “sukekuchi,” and “tsuyakieme” are used.

Wanting to open up new possibilities for lacquer so that it is used in a connected way

―Crafts have a tendency to be bound by ideas about how things should be, the more so the more tradition the craft has associated with it. Because of this, there are some crafts that fail to be put to use in a wider variety of ways and end up dying out, unfortunately.

Tsutsumi: To be sure, the lacquer world has many techniques and ways of using lacquer that have been passed down from the old days. These techniques are wonderful, but unfortunately, even when craft exhibitions are held at department stores, most young people do not go to see them.

―When we see people using interesting or cool things, we somehow end up feeling we want to use that thing too. If we were to reconfigure our understanding of lacquer as a functional material, which changes our sense of aesthetics and values, I imagine that there would be a greater number of people feeling the need for this material, that research and development would move forward, and that we would be able to create a stable supply system for lacquer.

Tsutsumi: Exactly. So I want to open up new possibilities for lacquer.

―You use lacquer for finishing bicycles and skateboards, right! When I first saw you doing this, I was shocked by how cool it looked. These are products that young people will really want to imitate.

- A lacquered bicycle. The transparent-looking frame is so cool!

- Lacquered skateboards. Applying several coats of lacquer to the damaged areas gives the boards an artistic flavor.

Tsutsumi: Thanks so much. I find it interesting how, just like with denim and leather, lacquer gets more character as you use it, and it becomes something all your own. Lacquer is actually durable, and can be used for different kinds of objects.

―That’s surprising. I had a strong impression of lacquer being used for traditional lacquerware objects, so I had thought it could not be used on anything other than wood.

Tsutsumi: There’s lacquer that can be applied to glass, and there’s also spray lacquer that is shrink-resistant and drip-resistant. Lacquer works well with any material. As a lacquer store, it’s important for us to manufacture things to facilitate lacquer being used in a greater variety of ways. We are currently developing new products, working with private companies and research facilities in universities.

―If we have more people like you, teasing out lacquer’s potential and working to develop applications that go beyond the everyday, the world of lacquer is sure to become more interesting than it currently is!

Tsutsumi: I don’t want to make traditional crafts such as lacquer the special turf of craftsmen alone. By collaborating with other fields, I believe that products and uses for lacquer that we have never imagined will come into being.

Lacquer in circulation, close to our lives

―Listening to you, I’ve come to realize that lacquer has a variety functions and appealing features. Finally, I would like to ask about what you want to want to work on in the future.

Tsutsumi: I feel that the world would head in a slightly better direction if we had more people with a sense of value that appreciates an aged look. If we had people thinking that lacquer is kind of cool, we might be able to have people think that planting lacquer trees in something important, rather like surfers who love the ocean and who do beach cleanups, for example. So we want to work on getting people to think of lacquer in ways that make sense to them, through objects that are part of their lives.

―That’s why you combine lacquer with familiar objects, such as bicycles and skateboards.

Tsutsumi: I have an image of lacquer as something perfectly round. Lacquer trees do not grow in the wild easily. They’ve been grown around the areas where people live since Japan’s Jomon period. People grew the trees and put them to use. They developed lacquer techniques at the same time. They repaired their lacquer tools and vessels and used them. They connected this with the feeling of cherishing objects and the life of the trees… All of this was connected. I feel that ever since the old days, lacquer has had something like a big ring around it, something that connects all this activity and circles around it. Lacquer’s like this, and it’s really sad when it’s perceived as something distant from our lives, and ends up disappearing. So I’d like to work with interesting people around the world and think about a life with lacquer in it.

―What kind of projects are you developing these days?

Tsutsumi: We’re collaborating with surfboard shapers and pro riders working overseas, working to get the word out about the appeal of lacquer by creating videos about lacquered surfboards and BMX bikes. There’s a wooden surfboard known as an alaia that was used in Hawai’i before modern times. Finding out about the world-class surfboard shaper Tom Wegener, who crafts alaia boards, and his connection with nature and people made us want to produce lacquer alaia boards as an icon that considers the relationships between humans and nature.

Lacquer alaia and alaia being ridden. (All four photos shot by Tsutsumi)

Tsutsumi: Modern-day surfboards are made of resin and polystyrene foam, so they end up as trash that can not be returned to the earth. Lacquered alaia are made of recyclable material. When we were shooting in Australia, the beauty of lacquer and the wonderful quality of this material resonated with many people, irrespective of race.

―That’s really interesting. While the UN has SDGs (sustainable development goals), lacquer has been in use, circulating resources, since ancient times.

Tsutsumi: Surfing and cycling were selected as new events for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. In order to connect lacquer with the next generation, we’d like to search for new ways of using lacquer and its expressive possibilities, while combining it with things that are getting attention now.

―We will continue watching to see how you communicate the appeal of lacquer! Thank you so much for the interview today.

(Article: Yui Kitagawa / Photos: Hanako Kimura * Note: excludes photos stating “shot by Tsutsumi’)

Interviewee

Managing Director, Tsutsumi Asakichi Urushi lacquer shop

Takuya Tsutsumi

Born in Kyoto. After graduating Faculty of Agriculture, Hokkaido University and working in other industries, returned to Kyoto to take over the family business in 2004. Launched Urushi no Ippo in 2016 to protect Japanese lacquer. Produces booklets and distributes them to kindergartens, elementary school, and lacquer shops, and also organizes factory tours. Currently collaborates with artists working overseas, working on creating a new culture that combines extreme sports and lacquer.

Tsutsumi Asakichi Urushi lacquer shop

インタビュアー:MTRL KYOTO・FabCafe Kyoto マネージャー

木下 浩佑

After working as manager in the Kyoto cafe neutron and the Tokyo art gallery neutron tokyo, Kosuke Kinoshita came to organize creator’s workshops and exhibitions and facilitated collaboration with companies, schools, and local governments at Ikejiri Institute of Design Setagaya Monodzukuri School, a facility that makes use of an old school building. He has organized various projects in the MTRL Kyoto building, such as the launch of Fab space. He joined Loftwork in 2015, and has been involved with the management and planning of shop services at the creative lounge MTRL KYOTO since the startup phase. Kinoshita opened FabCafe Kyoto on the first floor of MTRL KYOTO in June 2017. His motto is to work as an intermediary for the promotion of interaction and emergence that go beyond locality and areas of specialization.

A note from the editor (Kinoshita of MTRL Kyoto)

For the third edition of this sporadic series, Dive into Material, I visited Tsutsumi Asakichi Urushi lacquer store, which is not far from MTRL KYOTO/FabCafe Kyoto, for an interview done while inspecting the factory.

Even before my visit, I had seen Tsutsumi’s bicycles and skateboards being used (to get to our shop, which is is located nearby) and was already really impressed with how wonderful they are, thinking that lacquer looks so amazing and that I’d like to try lacquering something that I own too! After the interview, I applied lacquer to the handle of a kitchen knife that I’d been using for nearly 20 years and that was, by now, rather worn out. Having had delicate skin since I was a child, I was a little worried about getting a rash at first, but I put on some rubber gloves and got the job done without any trouble at all. I found lacquer a really easy material to work with once I got to know it, just as Tsutsumi explained. While becoming familiar with the material and working with it myself, I was also made aware of how difficult it is to finish beautifully and of the depth and wonder of the detailed handiwork done by craftspeople working with lacquer.

In skateboarding, surfing, music, and other communities, admiration for cool people, objects, and styles extends to cover the entirety of each person’s life and sense of aesthetics. The scene and the culture develop from this passion and empathy. Having fun as we make the objects that we desire, we create something that is attractive within that scene. Friends and other people will come to be involved. I felt the power to give birth to this fundamental human desire in Tsutsumi and his way of working with lacquer.

Recommended Articles

Recent Articles

-

Interview

Creating the “New Normal” for the Future: What is the “Complexity” Necessary for Co-Creation Between Academia and Industry? An Interview with Professor Kouta Minamizawa (Part Two)

-

Exploring New Realms of Design with Academia – An interview with Professor Kouta Minamizawa about the potential of co-creation projects with Academia -(Part One)

-

REPORT:School of Fashion Futures